The landscape of educational technology is always evolving as tools become more affordable, accessible, and easier to use. Early adoption of computer-assisted instruction, CD-ROMs, and DVDs has given way to cloud-based platforms and web-delivered learning environments, enabling broader adoption in teaching and learning. Over the last two decades, the field has seen the rise of flipped classrooms, massive open online courses (MOOCs), serious games, open educational resources (OER), augmented and virtual reality (AR/VR), microlearning platforms, personalized and adaptive learning systems, and, most recently, generative artificial intelligence (GenAI).

As the technological ecosystem evolves, so too do the professional expectations for those working in the learning sciences (instructional designers, curriculum developers, instructional technologists, faculty development professionals, performance improvement specialists, learning and development specialists, and trainers). Employers now expect advanced technical competencies including eLearning authoring tools (Articulate, Adobe Captivate), video production and editing (Camtasia, Adobe Premiere Pro), fluency with multiple learning management systems (Canvas, D2L), graphic design, basic coding and website development, productivity suites (Microsoft Office, Google Workspace), survey and assessment design, and increasingly, AI-enabled tools. Keeping pace with disruptive and emerging technologies is becoming a baseline expectation rather than an optional skill.

This raises important questions: How do professionals acquire these competencies? Are graduate programs preparing students with the applied technology experience they need? How do professionals who do not complete formal training programs develop these skills? To what extent are organizations investing in employee upskilling?

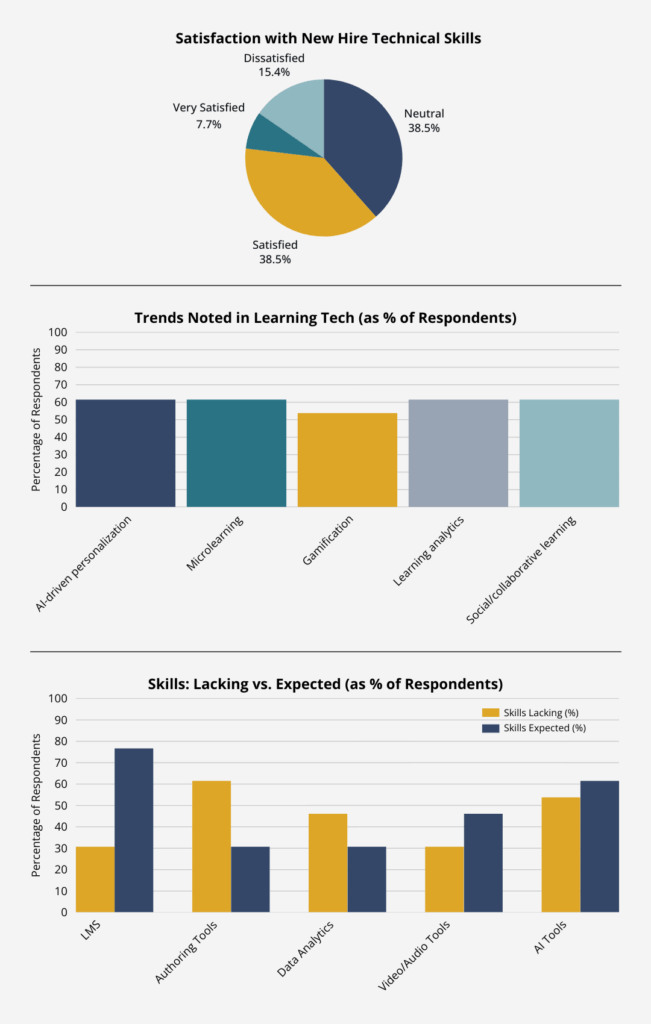

To explore these issues, we conducted an August Snap Survey (n=14), distributed across higher education and professional learning networks. The majority of respondents (86%) came from higher education contexts. While most respondents (86%) expressed satisfaction with their new hires’ technical skills overall, gaps were consistently identified in learning management systems, eLearning authoring tools, and AI-related competencies. Specifically, 79% of respondents noted a mismatch between expected and actual skills in learning management systems; 64% highlighted challenges with authoring tools; 57% identified AI skills as underdeveloped; and 50% flagged data analytics as an area of need. Interestingly, a few respondents noted that new hires lack skills in areas such as basic office tools (Excel, PowerPoint, etc.) and equipment usage such as laptops.

Organizations are addressing these shortfalls through a mix of professional learning approaches: on-the-job training (86%), internal workshops (71%), mentor/peer learning (64%), external conferences and webinars (57%), and subscriptions to platforms like LinkedIn Learning or Skillsoft (50%). These results suggest that while employers are generally satisfied with baseline competencies, they expect to provide substantial in-house training to close gaps in specialized technologies.

However, access to training opportunities is not uniform. Respondents noted that contingent faculty, part-time staff, and employees at under-resourced institutions are less likely to receive funded training or licenses for essential tools (e.g., Articulate 360). This raises equity concerns in workforce preparation and career advancement, particularly as organizations increasingly rely on certifications and demonstrable technology fluency in hiring.

Looking ahead, respondents identified AI-driven personalization (64%), microlearning (64%), gamification (57%), learning analytics (64%), and social/collaborative learning (64%) as the most influential trends in learning technologies over the next three to five years. This aligns with broader workforce studies (e.g., EDUCAUSE, Burning Glass), which also highlight digital fluency, data literacy, and ethical AI use as cross-sector priorities.

Taken together, the survey points to both challenges and opportunities. Graduate programs in instructional design and learning sciences may struggle to keep up with specific vendor tools due to budget constraints, licensing limitations, and the rapid turnover of technologies. A sustainable strategy is to emphasize transferable skills such as design thinking, data literacy, digital content creation, collaboration across platforms, and responsible AI use—skills that remain valuable even as specific tools evolve. At the same time, employers and academic programs can benefit from closer partnerships: co-developing curricula, offering micro-credentials or vendor certifications, and creating structured pipelines for continuous professional learning.

In an era of accelerating technological change, bridging the skills gap requires coordinated effort across academia, industry, and professional organizations. Focusing on transferable skills, equity in access to training, and agile program design will be key to preparing the next generation of professionals in the learning sciences.

As senior researcher at OLC, Carrie designs, conducts and manages the portfolio of research projects that align with the mission, vision, and goals of the Online Learning Consortium. She brings with her over 15 years of experience as an online educator and instructional designer with a passion for research. She has peer-reviewed publications covering a variety of topics such as open educational resources, online course best practices, and game-based learning. In addition to a strong background in higher education teaching and instructional design, Carrie brings with her extensive experience in customer service and small business management. She holds a PhD in Educational Technology from Arizona State University, an MS in French from Minnesota State University, and BA in French from Arizona State University.

As senior researcher at OLC, Carrie designs, conducts and manages the portfolio of research projects that align with the mission, vision, and goals of the Online Learning Consortium. She brings with her over 15 years of experience as an online educator and instructional designer with a passion for research. She has peer-reviewed publications covering a variety of topics such as open educational resources, online course best practices, and game-based learning. In addition to a strong background in higher education teaching and instructional design, Carrie brings with her extensive experience in customer service and small business management. She holds a PhD in Educational Technology from Arizona State University, an MS in French from Minnesota State University, and BA in French from Arizona State University.