“If you don’t know where you are going, any road will get you there.”

In considering digital modality definitions, Lewis Carroll’s quote reminds us of the feeling of empathy we have for Alice as she goes down the rabbit hole to navigate an often non-sensical world. Unlike the cryptic Chesire Cat, our goal is to use definitions as a map to help young students like Alice navigate the digital wonderland.

Thank you to OLC for tackling the sometimes “through the looking glass” evolution of digital learning modalities in its “Primer,” published in early July, on the resulting shifting and confusing array of definitions being employed. In championing the need for common definitions our previous work is cited in arguing that “(h)aving common terminology directly impacts how we design courses, how we measure outcomes, and how we set policy.” Most importantly, consistency in word usage is essential in communicating effectively with students trying to navigate the unfamiliar waters of course mode options.

Who Are Nicole and Russ?

“Who are you?” said the Caterpillar…Alice replied, rather shyly, “I—I hardly know, Sir, just at present—at least I know who I was when I got up this morning, but I think I must have been changed several times since then.”

After Nicole Johnson assumed the role as Executive Director of the Canadian Digital Learning Research Association (CDLRA), the former director recommended that she talk to Russ Poulin, who was then the Executive Director of WCET (WICHE Cooperative for Educational Technologies). Our resulting videoconference call discussing the intricacies of digital definitions revealed our kindred spirits and was as nerdy (in its own way) as anything you may have seen on The Big Bang Theory. We have had many more, equally nerdy, conversations and collaborations since. Please do not let that stop you from reading on, as we can tune it down.

Canada does not have a national higher education data survey like the U.S. Department of Education’s IPEDS collection. To answer questions about the growth and shifts in digital learning, the CDLRA was created to conduct nationwide surveys to effectively track digital learning trends. Such tracking is challenging when different institutions define the same term differently, Nicole has had to deal with finding definitions that speak to the most people and help respondents understand how their offerings fit into those definitions. Russ assisted with the creation of CDLRA and has long worked on definitions. Notably, he has twice served in Department of Education rulemaking committees or subcommittees that set definitions in federal financial aid regulations. He apologizes for the times he was outvoted on some of the language that made its way into official policy.

In 2022, we joined with Jeff Seaman (Bay View Analytics) in conducting a literature review and surveying practitioners on their level of agreement with digital learning definitions. One of the major findings of that work was that there was much more agreement on the definitions (e.g., online learning, hybrid learning) than any of us would have guessed. Those surveys and subsequent works on definitions were sponsored by WCET (see digital learning definitions page). A research paper was published in the OLC Online Learning journal.

In brief, we have thought deeply about modality-related terms for years.

So Why Can’t We Just Agree on Definitions?

“Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.” – The Queen.

Yes, there is agreement on the definitions as broad concepts. We have noted some problems in applying those concepts practically.

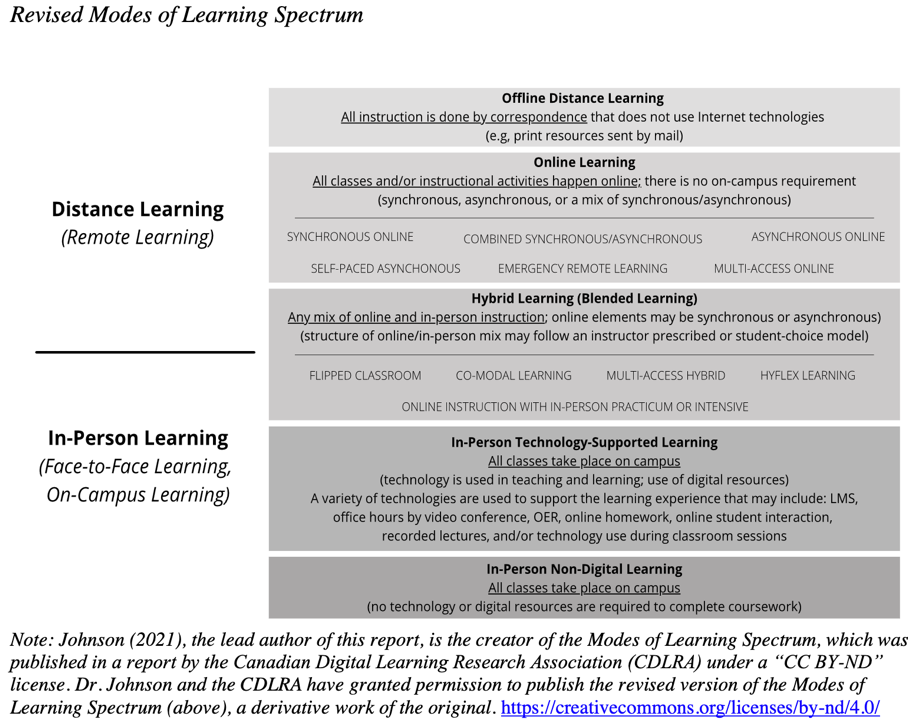

An old joke observes that there are two types of people in the world: 1) those that divide the world into two types of people and 2) those who do not. While mildly amusing, the joke reveals a truth in the complexity of creating stark dividing lines. Although there are still some clear-cut lines (e.g., an in-person learning experience is inherently synchronous), most learning experiences do not fall neatly within a single categorical box. As faculty become more comfortable and creative in using the technologies and teaching in various learning modalities, the distinguishing lines between modalities have become increasingly blurred. As a result, the difficulty of settling on definitions is compounded by digital learning now being a continuous spectrum of experiences rather than a collection of discrete choices. Figure 1 is taken from the paper published by OLC.

Figure 1

Image transcript for Figure 1

The infographic titled “Revised Modes of Learning Spectrum” is vertically divided into two sections: Distance Learning (Remote Learning) on top and In-Person Learning (Face-to-face Learning, On-campus learning) on bottom.

Starting at the top of the graphic, the Distance Learning section begins with “Offline Distance Learning,” where all instruction is done by correspondence that does not use internet technologies (e.g. print resources sent by mail). The next modality categorized as distance learning is “Online Learning.” With this modality, all classes and/or instructional activities happen online: there is no on-campus requirement (synchronous, asynchronous, or a mix of synchronous/asynchronous). Listed examples of online learning include: synchronous online, combined synchronous/asynchronous, asynchronous online, self-paced asynchronous, emergency remote learning, and multi-access online.

Moving down the spectrum, the next modality is “Hybrid Learning (Blended Learning),” which straddles the division between Distance and In-Person Learning. Hybrid learning is any mix of online and in-person instruction: online elements may be synchronous or asynchronous, structure of online/in-person mix may follow an instructor prescribed or student choice model. Examples of hybrid learning include: flipped classroom, co-modal learning, multi-access hybrid, hyflex learning, online instruction with in-person practicum or intensive. Moving down, the first modality fully considered in-person is “In-person Technology-Supported Learning.” With this format, all classes take place on campus, technology is used in teaching and learning; use of digital resources. A variety of technologies are used to support the learning experience that may include: LMS, office hours by video conference, OER, online homework, online student interaction, recorded lectures, and/or technology use during classroom sessions. The final modality and the furthest into the in-person side of the spectrum is “In-Person Non-Digital Learning”, where all classes take place on campus, and no technology or digital resources are required to complete coursework.

Outside of the graphic is a note: Johnson (2021), the lead author of this report, is the creator of the Modes of Learning Spectrum, which was published in a report by the Canadian Digital Learning Research Associate (CDLRA) under a “CC BY-ND” license. Dr. Johnson and the CDLRA have granted permission to publish the revised version of Modes of Learning Spectrum (above), a derivative work of the original. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/

A second problem is rooted in the historic nature of academic publishing and innovation. We call it definition creep where slight differences give rise to entirely new terms that often confuse more than illuminate. Reasons for the proliferation of terms include the need to publish “new” findings or simply being unaware of previous classifications. Russ recalls serving on a non-federal committee that was tasked with setting definitions. The committee used a “Christmas tree” approach and kept adding new wording with only slight variations. Not surprisingly, that work died of its own weight.

Finally, there is no unifying body who declares a definition to be the definition.

The OLC “Primer” Shows More Work is Needed

“Curiouser and curiouser!” cried Alice…”

While we applaud the intent of the OLC “Primer,” there are a few sections of it that highlighted the need for the two of us to remind everyone of the history and considerations involved in definitions work:

- Our original work was inspired by the need to identify the multiple meanings being ascribed to singular terms and, paradoxically, the singular meanings being ascribed to multiple terms. Whenever an entirely new term is used to describe a variation of a modality rather than an entirely new modality (e.g., bichronous), figuring out what people actually mean when they use a term becomes more complex.

- The explanation of “remote” learning did not fully address the emergency and unplanned nature of that form of online learning, especially as it occurred during the pandemic. To this day, we see critics using research from “emergency remote learning” to argue against well-planned and supported online courses.

- Colleges in the United States should be careful in using the term “self-paced” as it is a red flag to the Department of Education as “self-paced” courses violate “regular and substantive interaction.”

- Hyflex courses existed long before the pandemic.

- Some have strongly supported the term “bichronous,” but it seems to add yet another speed bump in student comprehension of what the course will entail. (As an aside, we question the overall relevance and usefulness of this term “bichronous.” Any well-designed synchronous online course would inherently include some asynchronous activities. We fail to understand (even after scouring the literature and arguments on the topic) how bichronous learning is any different from a typical synchronous online learning experience.)

A Call to Action

“My dear, here we must run as fast as we can, just to stay in place. And if you wish to go anywhere you must run twice as fast as that.”

We think it is time to do something about this. We are working on a plan for a group of organizations and government agencies in Canada and the United States to form a loose coalition to address these issues.

Our initial principles in performing this work are:

- Focus on the students. Definitions should focus on communicating to the student the experience they will have in the course and related requirements. Are there any in-person requirements? Are there synchronous requirements? Are technologies needed?

- Less is more. Creating a new term to describe a learning experience that is captured well-enough by the existing terminology only creates more confusion for students and faculty, and it adds to the margin of error for broad-scale research efforts.

- Simple is better. Some definitions have become quite complex.

- The spectrum of options is real. We need to address when dividing lines are absolute and when there is flexibility. This means that we will probably need to address only a few definitions as broader constructs that allow other terms to be folded into the overall structure.

The digital modalities primer published by OLC inspired us to reignite our research work on definitions. Some of the questions we are eager to explore include:

- What are the most common forward-facing terms that institutions use when describing different modalities to students?

- To what extent are forward-facing terms understood and applied within institutions?

- Which terms describe a spectrum of experiences and which ones are (or should be) absolute?

We are committed to a student-focused approach.

We are working on our plan.

We invite your input and interest.

Executive Director

Canadian Digital Learning Research Association/

Association canadienne de recherche sur la formation en ligne

With more than two decades of experience in the field of education, Dr. Nicole Johnson is a leading expert in macro-level digital learning trends. As the Executive Director of the Canadian Digital Learning Research Association (CDLRA), she leads annual, longitudinal research studies exploring technologies and practices related to digital learning at post-secondary institutions. She also has an independent research and consulting practice, helping clients develop future-proof strategies and policies for technology use in teaching and learning. Along with her work on digital learning trends, Dr. Johnson’s research experience includes examining the implications of artificial intelligence in education, exploring potential futures for higher education, defining and operationalizing key terms associated with digital learning, investigating faculty experiences with technology, investigating the use of open educational resources (OER), and understanding how adults learn informally in digital contexts. She has authored and co-authored over 30 publications related to digital learning trends and digital transformation (including journal publications specific to artificial intelligence) since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.