A SCENE, NOT A HASHTAG

I first saw #IndieEdTech on a Tom Woodward tweet, which may be why it caught my attention. I work with Tom at Virginia Commonwealth University’s Academic Learning Transformation Lab and have never known him to be a casual hashtagger. As I contemplated the hashtag, I remembered he was attending the Indie EdTech Data Learning Summit, a meeting on personal APIs hosted by Davidson College, a meeting so low key it had escaped my radar entirely until I was trying to track down Tom and Jon Becker, who were both there. A couple more #IndieEdTech tweets from the likes of Jim Groom and Kristen Eshleman…yes #IndieEdTech was being used as a conference hashtag.

Most conference hashtags are limited in scope, meant to help conference participants find each other, pass on conference announcements, identify trends and climate, and contextualize tweets. Furthermore, most conference/meeting hashtags are (literally) dated. #ELI15. #AACUGenEd16. #NLC2016. Have you ever followed a TAGS Explorer of a conference hashtag? Their use drops off significantly once attendees get home and then typically disappear altogether once they have written their post-conference reflections.

But #IndieEdTech is more than a conference hashtag. I (we) need it to be something more.

I attended the College of William and Mary in the late 90s. At the time, there were no bars in Williamsburg because city ordinances required all alcohol-serving establishments to include full kitchens and table service. Instead, students hung out at the “delis,” a row of bars-serving-meat-subs-and-cheese-fries across from campus. While the delis served the same food in the same format, each one represented a different scene: College Deli was for the greeks and underage drinkers, Greenleaf for faculty and law students, Momma Mias for loners and shady dealers, and Paul’s Deli for students who tended to follow the rules. Your deli was your hangout, but it was also your calling card. To say that my crew and I closed Paul’s most nights of the week meant something to others as well as to ourselves.

Hashtags are virtual pinboards and meeting spaces, but they can be a demonstration of identity as well. Many academic tweeters list hashtags in our Twitter profiles to signal something about ourselves. In college I was Paul’s Deli. Now I am #connectedlearning, #opened, and #highered. My hashtags are my “scene” and my scene says a lot about who I am, who I hang out with, and what I believe.

TIME FOR A THINGVELLIR

We don’t know what #IndieEdTech is yet. In terms of the trending IndieEd Tech movement, Audrey Watters wrote a blog post on it last year. Adam Croom and Jim Groom have presented on it. The focus seems to be on personal APIs – taking back digital spaces from schools and learning management systems and the like and giving them to the students to craft, use, and own in their learning in any way that they like. Kristen Eshleman reflected that Indie EdTech is about the individual. Ok, that’s fine. It draws on underlying principles of academic freedom and student agency and we know I can get with that. However, I’m not sure it’s enough to think about #IndieEdTech through the lens of student agency.

I just returned home from #OLCInnovate (reflection coming shortly). One of the highlights for me was Rolin Moe’s museum installation, which challenged our perceptions of innovation right there from the center of the vendor hall. We generally think of innovation as a good thing, but Rolin used his platform to present innovation as a more complex concept. When we reflect on what innovation means (which occurs infrequently anyway), we tend to think about what innovation means to us as individuals. We fail to consider what innovation means to us as a community of educational technologists. He suggested that we should be working towards a deeper,more collective understanding of why we create change so that we might make more of an impact.

The Indie EdTech Data Summit notwithstanding, I think it’s time for more of us as a group of educational technologists to think about, explore, and describe aspects of Indie EdTech – collectively. Furthermore, while I think it’s important to keep the student (or the individual, really) at the center of the discussion, there is absolutely nothing wrong with exploring it from a relational perspective, either. In her keynote for the summit, Audrey Watters stated she didn’t want to talk about indie versus industry. Ok, that makes sense too, because no one ever got anywhere by pitting two groups together (at least no one I ever cared to know). However, I want to talk about indie in relation to the establishment – I’m not talking about business models here, I’m talking about people and how they relate. To do so might scaffold some mutual understanding, self-reflection, and strategies for moving through the educational world as we know it.

THE INDIE CONNECTION

So what is #IndieEdTech? While Jim Groom and Adam Croom tend to talk about Indie EdTech in terms of the indie music scene, I prefer the film industry, in part because it offers a useful narrative around the relationship between independent and establishment filmmakers. Much of the summary provided below comes from a synthesis of this wikipedia article, this blog post, and this website.

In 1908, nine major American film companies joined the leading film distributor and film stock producer to create the New Jersey-based Motion Picture Patents Company (MPPC). The group, also known as the “Edison Trust,” ended foreign dominance over the domestic film industry by standardizing film distribution and production. However, MPPC patents made it difficult for other U.S. film companies to operate.

Many of these “independent” filmmakers moved west, settling in Hollywood, California, where local court systems had little interest in policing copyright policies for east-coast businesses. Out there on their own, these filmmakers built their own equipment, explored alternative business models, and experimented with a longer “feature film” format. In contrast, MPPC producers were reluctant to explore feature film despite positive public response to indie products. Instead, they used their resources to perfect the status quo: the shorter format film.

When World War I limited their foreign market and anti-trust laws disrupted their monopoly, MPPC had to shut down in 1918; among other things, they were being outperformed by the indie filmmakers. The independent filmmakers, who by this time had created the studio system, established their control over the mainstream market and ushered in the golden age of Hollywood film. They became the new establishment.

Even in the golden age, new independent filmmakers emerged supported by United Artists and similar groups. World War II triggered a new wave of trustbusting and tech, which included smaller, cheaper, more accessible cameras. Suddenly, filmmaking was an activity “of the people,” and many were able to take bigger creative risks with low budget features. Meanwhile, major studios perfected the “specatacle,” incredibly expensive, unabashedly big epics and musicals that spoke to the aesthetics and dreams of an aging audience. A new wave of trustbusting and disruptive tech (this time, television) threatened to topple the major studios, but they recovered (somewhat) by quickly appropriating indie talent and techniques. Bonnie and Clyde, Midnight Cowboy, and The Graduate evoke the indie aesthetic, but were all major studio films.

THE CYCLE OF DEPARTURE AND APPROPRIATION

What can we learn from the story of indie films? First, an intimate and cyclical relationship exists between the establishment and the indie. The former deals in a known narrative that many people find comfortable and easy to understand. The latter exists because they are either excluded and/or they need something different to be happy. The establishment tends to pour its resources into refining or improving what it already knows. MPPC focused on the short film format. The aging studios made spectacular flops. The ed tech establishment sells next generation learning management systems and publishes on learning analytics. The establishment’s obsessive quest for “best practice” assumes a uniform and frequently narrow context; this makes it vulnerable in the presence of social or institutional disruption. In these instances, the establishment either appropriates indie innovation or crumbles, leaving indies to fill the vacuum.

THE ART OF (IN)APPROPRIATION

The cycle described above involves the departure of the indie from the main scene. Some people use the punk scene to describe this process – as a scene, punk rock is openly angry, rebellious, and tends to position itself in direct opposition to the establishment. Some indie films are the same – there’s an entire subgenre of dystopia out there. However , indie doesn’t have to be dystopic. Indie can involve the practice of (in)appropriation, remixing and repurposing aspects of the established narrative to transform it into something entirely new. Not opposite…different. Not angry…curious.

I spent some quality time at #OLCInnovate talking about this with Adam Croom. He worries that people might conceptualize #IndieEdTech through a single lens, specifically, the opposite or the reflection of the establishment. We agreed that it’s important not to think of indie through a single platform, tool, or practice.

Let me be clear: my #IndieEdTech is not about personal APIs. It’s about how students and faculty interact with the open web and how we can explore it together. As Adam mentioned in his last post, he and I have a very honest relationship. He knows better than to throw a specific digital tool at me without brainstorming with me about how it can transform the learning experience. My point is that you don’t have to be a GitHub or Wikity expert to be #IndieEdTech. I mean, you could be, but you don’t have to be. #IndieEdTech is bigger scene than that.

THE TENSION BETWEEN AUTHENTICITY AND SCALABILITY

By definition, indie is uncomfortable for many mainstream audiences because it tends to trigger a visceral response to things we usually ignore. When indie artists seek scalability, they are often faced with demands to regress to the mean, soften the edges, compromise their creative integrity. For some, the tension between authenticity and scalability becomes too much and they exit the game. The Filmmakers Cooperative, for example, refused to work in or with Hollywood because it was “morally corrupt and aesthetically obsolete.” Some indies are separatists, punks, the avant garde of film who make beautiful things for niche audiences (often overseas). Above all, they are true to their authentic selves but at the cost of scalability.

THE POTENTIAL OF CONNECTED LEARNING AND UNIVERSAL DESIGN

But what if scalability didn’t have to mean a single narrative, a regression to a singular mean? A learning management system? What if we can work within paradigms such as connected learning or universal design for learning, which foster educational inclusiveness and student engagement through the diversification of pathways to academic success? Jon Becker and I are currently writing on how connected learning presents a compelling method for implementing UDL principles.

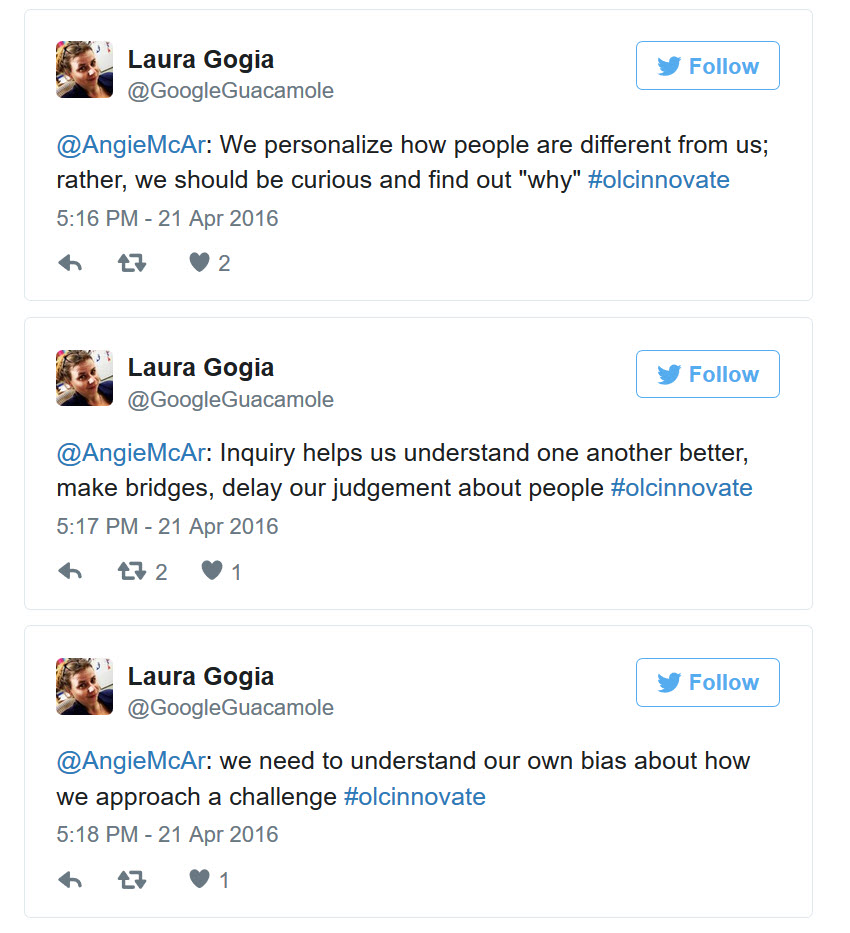

As our #OLCInnovate keynote speaker, Angie McArthur argued, valuable collaboration does not occur when people automatically agree to a single narrative. Her keynote, essentialized:

CONCLUSION: THE SPIRIT OF INDIE

Indie has been described as a “maddeningly elusive term.” There is history to the term, indie and it goes something like this… Individuals who lack a voice in or whose needs are not met by the establishment will separate themselves from it. They begin to explore (or innovate) alternative approaches. Indie involves thinking differently, not necessarily better. Indie implies risk. It is inherently diverse. Indie is about organic upstarts, each with a do-it-yourself ethos and a dedication to trying something different. None are exactly the same.

Being indie is not necessarily a disruption, but can be a reflection, a transformation, an offering of alternatives. It is about embracing the awkwardness of difference and accepting a multitude of approaches in terms of format, content, information positioning, and distribution.

Being indie means being yourself, but for me, it also means being in the presence of and in relation to others. I look forward to a bigger, broader, inclusive discussion.

I am #IndieEdTech. So are you.

About Laura Gogia